- Dan Kois is an editor and writer for Slate, and a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine. He and his wife – attorney Alia Smith – found themselves stressed and itching to get out of their “parenting bubble.”

- In 2017, they decided to uproot their lives in Arlington, Virginia, and take their two daughters to New Zealand, the Netherlands, Costa Rica, and Kansas to experience how families lived and coexisted.

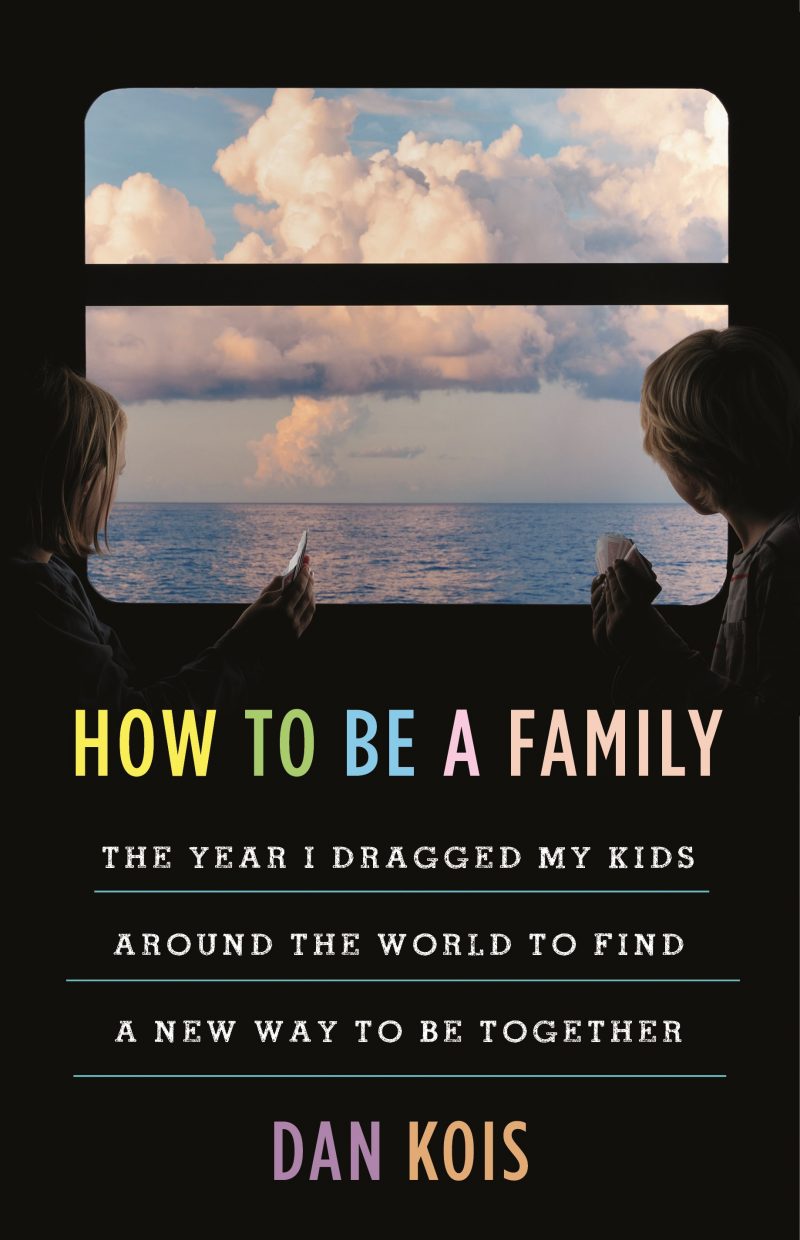

- During their travels, Kois wrote a memoir documenting their experiences: “How to Be a Family: The Year I Dragged My Kids Around the World to Find a New Way to Be Together.”

- In an interview with Business Insider, Kois said he would recommend a similar experience to a family considering a change.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Overburdened by the East Coast “parenting bubble,” Dan Kois and his wife uprooted their family’s lives for a year.

In 2017, they fled Arlington, Virginia for New Zealand, the Netherlands, Costa Rica, and Kansas. Their goal was to learn how local families lived, coexisted, and educated their children.

Kois wrote about his family’s experiences in his recently published memoir, “How to Be a Family: The Year I Dragged My Kids Around the World to Find a New Way to Be Together.“

Kois, a writer and editor at Slate, is married to attorney Alia Smith. In 2016, the two found themselves struggling to find a balance between demanding jobs, the tribulations of American daily life, and trying to parent their two pre-teen daughters, Lyra and Harper.

"Our family wasn't broken or dysfunctional, but we were in an unhappy rut, one that seemed of our own making but was also tied to the busy, hyper-competent parenting culture that surrounded us in Arlington," Kois wrote.

Kois and Smith felt "trapped" in this parenting bubble. So they took drastic action and charted a new course for the next year.

They would spend it traveling the world, settling down in four different places to get a taste of their parenting styles and overall lifestyle.

"The goal of the trip was to give our family an experience together in which we have no choice but to get together as a group, do the things that were hard for us, and and have an experience that could change us in some way," Kois said in an interview with Business Insider.

First up was spending January through mid-April in Wellington, New Zealand - Kois' favorite of the four destinations.

Next was the city of Delft, Netherlands, where they stayed until early July.

After that was what Kois and Smith decided was "summer vacation" - July through September in Sámara, Costa Rica.

They concluded their year back in the US, this time in Hays, Kansas. The town has an area of 8.4 square miles and has a population of a little less than 21,000 - a bit of an adjustment from the approximately 237,500 people in Arlington, Virginia's 26 square miles.

Looking back on their travels, Kois said he would have gone about planning it differently.

"I mean, I wouldn't recommend that you be quite so stupid about it," Kois said.

Now, nearly two years after moving back to Arlington, Kois is on tour promoting his book and thinking about what impact the trip left on him and his family.

Kois said that he would recommend a trip in the same spirit to anyone considering it, but his experiences taught him a better way of planning major family decisions.

Going into their journey, Kois and Smith made a unilateral decision to uproot their lives - and the lives of their daughters, Harper and Lyra.

That meant bringing them to exciting new locations far and wide. But it also meant starting in three different schools, and leaving home behind.

When Kois and Smith first told the girls about the plan to spend the year traveling, they were met with excitement and apprehension. Their younger daughter, Harper, immediately began helping to prepare, while their eldest daughter, Lyra, pushed back at times on being made to do something she had never asked to do.

One concept Kois learned in the Netherlands is the Dutch poldermodel. It is a philosophy of cooperation, one used in both business and familial settings. At its essence, poldering means that all group members deliberate - for as long as it takes - until they reach a decision that everyone is satisfied with.

"Dutch people love rules in part because they had a say in creating them," Kois writes.

This doesn't have to be a decision that everyone agrees is the best one, but simply one that garners broad consensus. The poldermodel has been "adopted enthusiastically" into Dutch family life, Kois writes - and he and Smith began to practice it during their time there.

Retrospectively, Kois said that poldering with their children before setting out for a year may have made their trip smoother - and smarter.

"If we had sat down and talked about this year long trip with our kids before we went on it, if we had poldered it out with them, we would have averted, I think, a lot of heartache and arguments and bad days," Kois said.

One pressure point for the family was the different educational systems their daughters attended. For their older daughter, the Dutch system proved to be particularly difficult.

Kois' eldest daughter, Lyra, encountered the downside of poldering in her Dutch classroom. The group had already decided upon rules before she arrived, meaning she had no say in them.

In the book, Kois describes the significant cultural and social differences between the Dutch and American systems. The American system broadly fosters and prizes individualism, while the Dutch practice a "rigorous equity."

"Dutch schools are dismissive of individual achievement and admirably concerned with fostering an environment in which every child is treated the same, as a part of one well-operating classroom," Kois wrote.

But that didn't translate to a smooth classroom experience for Kois' outspoken daughter, who was facing the additional challenge of a language barrier.

As a kid "who's very particular and very vocal and does not like what she sees as unfairness or injustice, like many American kids who are not afraid to speak up about it, she basically broke her classroom," Kois said.

"Our sort of big overarching takeaway is the kids can basically survive almost any educational system you put them through," Kois continued.

People frequently asked how they made the trip work financially. Kois said there was 'a very explicit trade of money for time.'

Kois said he's frequently asked about how the finances of the trip worked. Now that they're on the other side of their travels, there's a fairly simple answer.

"We don't have any money," Kois said. "I mean we spent all our money, we spent most of our savings."

To prepare for their year, Kois said they saved as much as they could. While on their travels, they brought in income from two books Kois was writing - including the memoir - and Smith continued her work remotely, albeit more sporadically.

They rented out their home in Arlington for a little less than their mortgage payment, and sought out "economical" places to live in their new home bases. They sent their children to public schools and tried "not to make horrible mistakes."

Ultimately, a beloved library in Hays, Kansas revealed something fundamental about community.

After Lyra's first day of school in Hays, Kansas, she and Kois headed through the tiny downtown to the local library. They would end up going there "almost every single day."

"The Hays Library is a public good funded by a tax levy that the people of Hays voted on themselves, run by optimistic, ambitious twenty-five-year-olds, open to all, a home for teenagers where their parents cannot hassle them," Kois wrote. "It is glorious."

Kois recently returned to the library for an invited reading. He described it as "like a miracle."

The library's role in Hays became one of the lessons that Kois retains from his travels.

"I think every place probably in the world has something like that," Kois said. "Has a place that - by design or by accident or by some combination of the two - has turned into a little oasis for, and a little center - like a locus of the community' for the people who live there. In Hays' case, it was a library."

Kois said that parents don't need to move around the world for a year to reap similar rewards. Instead, the ethos of the trip is what matters - and what he recommends.

"I think the real lesson of the trip for us - that I feel like other families can take away from - it is not that you need to go away for a year to four different countries for three months, and write a stunt book," Kois said. "The lesson is that you should find the thing that you want for your family, and the thing that seems difficult for your family, and you should do it."